Some Sundays, when Charles Moore goes to church, he finds himself sitting behind a professional or college athlete. And he starts to wonder: What kind of gambling education is that player getting? Will he be harassed if he blows a play? What can I do to help?

Charles Moore is the executive director of the Wyoming Gaming Commission (WGC). Casper, population of 58,543, is the second-biggest city in the least populous state in the US. It is also Cincinnati Bengal Logan Wilson’s hometown.

Wyoming’s current athletic claim to fame is Buffalo Bills starting quarterback Josh Allen, a University of Wyoming graduate. There are four active NFL players who went to college in Wyoming and one active NBA player (Larry Nance Jr). New York Met Brandon Nimmo is a native of the state’s biggest city, Cheyenne (population 64,795).

Does harassment have a “direct relationship” to props?

Each one of them is on Moore’s mind.

“We know for a fact that our student athletes are being harassed,” Moore said. “And we know that happens in the NFL. But how do you weigh that against someone who placed a prop bet? We know they are getting harassed. It happens at Little League. But how much of it is a direct relationship to prop bets?”

That’s a good question and one not easily answered. In recent months, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has been asking states to ban prop bets on college athletes. The agency says it wants to protect student-athletes. Louisiana, Maryland and Ohio are among a handful of states that have responded to the call.

College player prop betting is finished in Ohio as of March 1. Matthew Schuler, executive director of the Ohio Casino Control Commission, announced today he approved the NCAA's request to ban such wagering. Any remaining futures must be voided by next Friday. pic.twitter.com/b9MXDJmZJE

— Geoff Zochodne (@GeoffZochodne) February 23, 2024

“The NCAA is doing more than ever before to protect student-athletes and the integrity of competition from the harms of sports betting and would like to see all states ban individual player prop bets on college competitions from their books,” the NCAA said in a statement. “The Association has been working with states to deal with these threats and many are responding by banning college prop bets.”

Maryland and Ohio instituted the new prohibition on 1 March, ahead of the NCAA post-season basketball tournaments. Louisiana’s ban goes into effect on 1 August. There are other states, including Arizona, Massachusetts and New York, which opened their markets with a ban on college-player prop bets in place.

Lack of data an issue

Moore’s WGC was contacted by the NCAA and the University of Wyoming and asked to consider a ban. The agency will hold its first informational meeting on the topic on Thursday (9 May).

“We’re not going to say ‘no’ to the discussion,” Moore said. “I think at this point, there is not a lot of information. I think we are still in this situation where we want to hear more. Honestly, I don’t know where it’s going to go or where it needs to go. And that’s because I believe there is a lack of data.”

Moore isn’t the only one. There is virtually no data available to show if or how college or pro athletes have suffered because prop bets are available. Anecdotally, major legal US operators only offer prop bets on college baseball, basketball (men’s and women’s) and football. Some don’t even offer the bets on baseball, because it is a niche sport.

One source said that 85% of the collegiate prop bets placed are on roughly 100 student athletes. Many of those 100 are the most recognisable student athletes in the country with significant name, image and likeness (NIL) deals. According to the NCAA, as of 2021-22, its member schools had more than 520,000 student-athletes. Of those athletes, 192,103 played a sport at a Division I school.

One industry source who requested anonymity called the NCAA’s effort “taking a baseball bat to swat a fly when you need a fly swatter”.

NCAA playing politics?

Some view the NCAA’s desire for a ban strictly as a political move. One referred to the ban as “low-hanging fruit”. Saying that it will protect its athletes at all costs isn’t a stance anyone will oppose, stakeholders say.

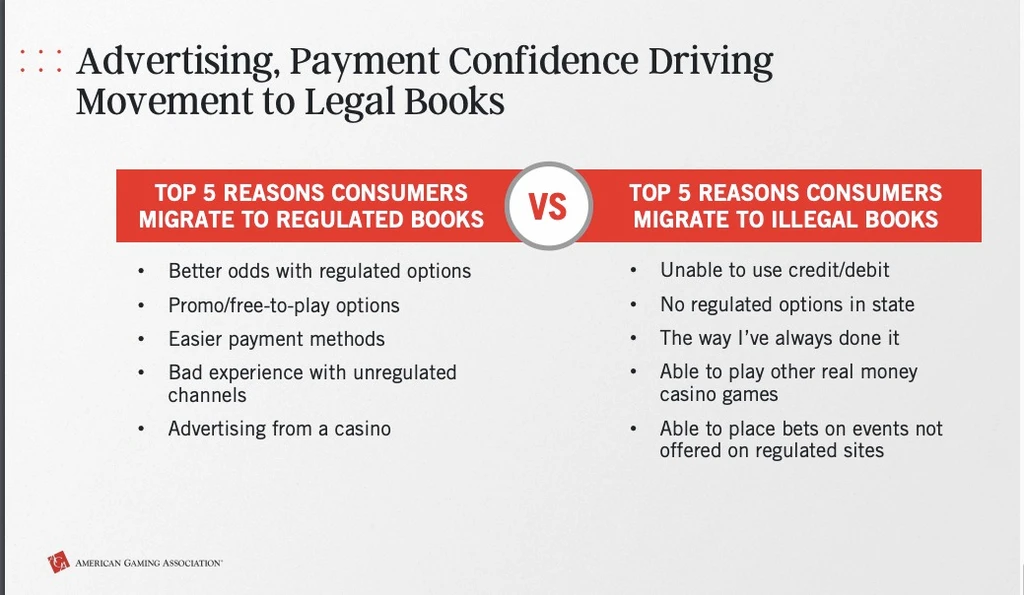

“All you’re doing is shipping everything to the illegal market,” said Brendan Bussmann, principal for the gambling consultancy BGlobal. “The NCAA pulled its head out of the sand and is doing everything it can to put lipstick on a pig. [NCAA president] Charlie Baker is getting a lot of political mileage out of something that is a hill he is going to have to die on later.”

Baker, the former Massachusetts governor, joined the NCAA last year. He is no stranger to politics and the NCAA isn’t generally viewed as a warm-and-fuzzy institution. The hire was calculated and this issue has the potential to buy a lot of political capital with the agency’s member schools and student-athletes.

“I see what the NCAA is doing, playing politics and trying to get the public to take its side,” the anonymous source said. “Charlie Baker is a skilled politician. This is part of the brand rebuilding exercise that the NCAA is going through.”

College-athlete harassment is not new. Michigan’s Fab Five lost two NCAA championship games, including one widely remembered for Chris Webber’s timeout, which cost them the 1993 title game against Duke. After that game, the team dealt with “backlash” and “racist and hateful” mail, according to The Guardian. At that time, sports betting was, for the most part, illegal. The NCAA did not step in to curb the abuse.

“The NCAA needs to take a more proactive response,” Bussmann said. “As I talk to teams and leagues about this subject, they are trying to understand the market versus Charlie Baker. The NCAA has been ignoring this issue for more than 20 years, but [Baker will] take it as a political victory.”

Harassment isn’t OK, but banning props just one step

Politics aside, stakeholders agree that while the number of athletes in question is a minuscule percentage of the whole, they should be protected.

“The sports betting industry doesn’t support student-athlete harassment,” the anonymous source said. The industry “is actively working with regulators to ensure that they are putting rules in place to root out the bad actors, as exemplified by Ohio and West Virginia”.

But many wonder if banning prop bets will have the desired effect.

“I feel that banning prop bets is only one piece and, if we don’t educate more about betting and how to deal with these nuances and new issues, it’s a systemic failure,” problem and responsible gambling consultant Brianne Doura-Schawohl said.

Jordan Bender of JMP estimates the NCAA-backed ban on college prop bets would remove $200mm from the legal sports betting market to the benefit of illegal books.

"At the end of the day, bettors will find a way to wager on events and players, and we believe the effort to ban… pic.twitter.com/71dUgUEuhO— Chris Grove (@OPReport) March 28, 2024

The idea of a college prop-bet ban raises multiple questions for the wagering industry. Any operator wants to offer as many markets as possible. Some say eliminating a market sends bettors offshore, where they are no longer protected or even guaranteed to be paid.

“Player propositions are available on illegal and offshore sportsbooks and removing customers’ ability to place legal wagers will deter bettors from moving to the regulated market,” American Gaming Association SVP strategic communications Joe Maloney said. “Our industry strongly supports the universal and shared goal of reducing athlete harassment and preserving integrity and we look forward to constructive dialogue with gaming regulators and other stakeholders to ensure robust legal sports betting markets maintain regulatory safeguards that protect consumers, athletes and game integrity.”

Illegal markets will offer whatever makes them money

There is no data available to show that banning any market sends players offshore – or to a neighbouring state. There is data that shows that the average US sports bettor has about three apps on his/her phone. So if a bettor who has been betting in a legal market goes offshore for a bet and downloads a new app, it seems likely the bettor will delete one of his legal apps and that operator will lose the business.

“It’s reasonable to assume that illegal sportsbooks will offer markets like college player props if consumers have significant interest in the markets,” sports betting industry investor and executive Chris Grove said. “That assumption is especially reasonable if offering those markets provides illegal sportsbooks with a competitive advantage over DraftKings or FanDuel.”

If you accept the idea that players will go offshore to find banned markets, then banning college-player prop bets won’t solve the NCAA’s problem. Betting will continue on more college players than legal markets offer.

“If there isn’t significant consumer interest in college player props, it is unclear why the NCAA is concerned about such markets,” Grove said. “So either college-player props are popular and illegal operators will offer them, or they’re not and the ban doesn’t address a material harm.”

Harassment is a “cultural thing”

Whether a bet is placed legally or offshore, society seems to accept the harassment of players because of failed bets. That, some say, is where the real problem lies.

“I think it’s definitely a social/cultural thing,” said Susan Sheridan Tucker, board president for the National Council for Problem Gambling. “Look at the way people are reacting to everything. Social media has opened the Pandora’s box to people’s unbridled responses. While the threats might not be executable, the fact that someone thinks they can threaten a college athlete, well, my goodness!

“An adult who is placing a bet and loses, to blame the athlete? There is no accountability.”

Sheridan Tucker and Doura-Schawohl say that prop bets and microbetting can “exacerbate problematic play”. But both agree that that type of betting alone isn’t to blame. Being able to bet from a device and a society that accepts bad behaviour are also key issues.

Some states banning harassers

Since sports betting has become legal, Doura-Schawohl said, it has created a situation in which disgruntled bettors are more likely to speak out.

“If you’re an angry bettor and betting is illegal, you are less likely to own that and say anything,” she said. “Now it’s easier to say, ‘Hey, you hurt me.’ Because now they are doing something legal. We also live in a culture where there is a lot less editing and filtration of what is out there.

“There is data that shows that increased betting leads to harassment, but that is also a cultural issue that comes from the proliferation of social media.”

In Ohio and West Virginia, those caught harassing college and professional athletes will be banned from betting on the legal market. But they can still bet offshore, so it will take more than regulators cracking down to stop harassment.

“If the gaming industry decided to penalise people, that would be a good thing,” Sheridan Tucker said. “We have to reach the point where this can’t be tolerated and enough is enough.”

How NIL now plays into NCAA sports

This year, incidents of well-known harassment have turned up in Ohio and North Carolina. Cleveland Cavaliers coach JB Bickerstaff got threatening text messages from a bettor. North Carolina star Armando Bacot said during the NCAA tournament that he got “over 100 messages from people telling me I sucked and stuff like that because I didn’t get enough rebounds. I think it’s definitely a little out of hand.”

Will Zach Edey score more than 25.5 points? Can Paige Bueckers grab more than 6.5 rebounds? How many 3-pointers will Caitlin Clark drain?

As the Final Four nears, there is intensifying scrutiny on the dangers of college prop betting.@EricPrisbell: https://t.co/m0cP0662Qo pic.twitter.com/bLSkMzzc66— On3 NIL (@On3NIL) April 4, 2024

Bacot is in that small group of players who have a big enough name that prop bets on him are offered. Part of the way he gained that name recognition is through NIL deals.

The ability of well-known college players to make money through NIL deals has boosted their bank accounts and celebrity. Bacot has deals with Dunkin’ Donuts, Frosted Flakes and other companies that result in a reported $1m in compensation.

That number doesn’t touch the reported $3.1m Iowa’s Caitlin Clarke earned through NIL deals. USC freshman basketball player Bronny James – LeBron’s son – has so far earned $4.9m.

Culture change needed to protect athletes

Doura-Schawohl say athletes who are harassed “feel their world is crashing down”. Some don’t know how to handle the pressure. She and others agree these athletes should be protected. But she says banning prop bets is just the beginning.

“If we don’t educate more about betting and how to deal with these nuances and new issues, it’s a systemic failure,” she said. “States really need to double down on the harassment piece.”

The NCAA is calling for a ban on prop bets, citing competitive integrity & increasing player harassment.

Illinois HC Brad Underwood: “I would hate to see the day where nobody jumps for the jump ball because of a prop bet.“ pic.twitter.com/8EeBF1v5sU— Michele Steele (@MicheleSteele) March 27, 2024

One source representing an operator who asked not be named was more direct: “Everyone hates this kind of behaviour. Fundamentally, I think you have to tackle the behaviour itself and change the culture that doesn’t challenge that behaviour – make it so that fans are comfortable telling each other ‘look, what you said is not cool’.

“Leagues, teams, sports media, associations, operators all have the same interest here. Some type of organisations push to say, essentially, ‘dude, don’t be an asshole’ and make fans feel ok to call out others who cross the line. That’s the kind of attempt at culture change that seems much more likely to actually the address the problem than simply moving prop bets from the legal to the illegal market.”